Paul Auster died on Tuesday.

-

How is it possible to miss someone we never knew? I keep asking myself these last couple of days. Are we entitled to a loss that suddenly feels so intimate?

We mourn the writer we claim we knew, but the actual human being unknown to us is graciously left to be mourned as is proper by his family and friends, by those who knew him, who lived and worked with him. We readers are left with his books, his words that stay to haunt us, his words we read again and again, words that shape us every time into something new, malleable beings that we are.

I remember myself in front of a bookshelf, in a past – distant as that girl who stood there that day picking up two books. One of these was ‘Leviathan’, let the other remain a mystery for now. Both books changed me in ways I could not have foreseen. His books, I kept on reading throughout the years. Some I liked more, some I liked less. I am not here today to write book reviews. I am not going to explain why or how much I loved these books or the screenplays he wrote for the movies I still like to watch; such private matters are best to stay private. I only want to tell you it is one of his books that has brought me here in the first place – the first book I ever read in English.

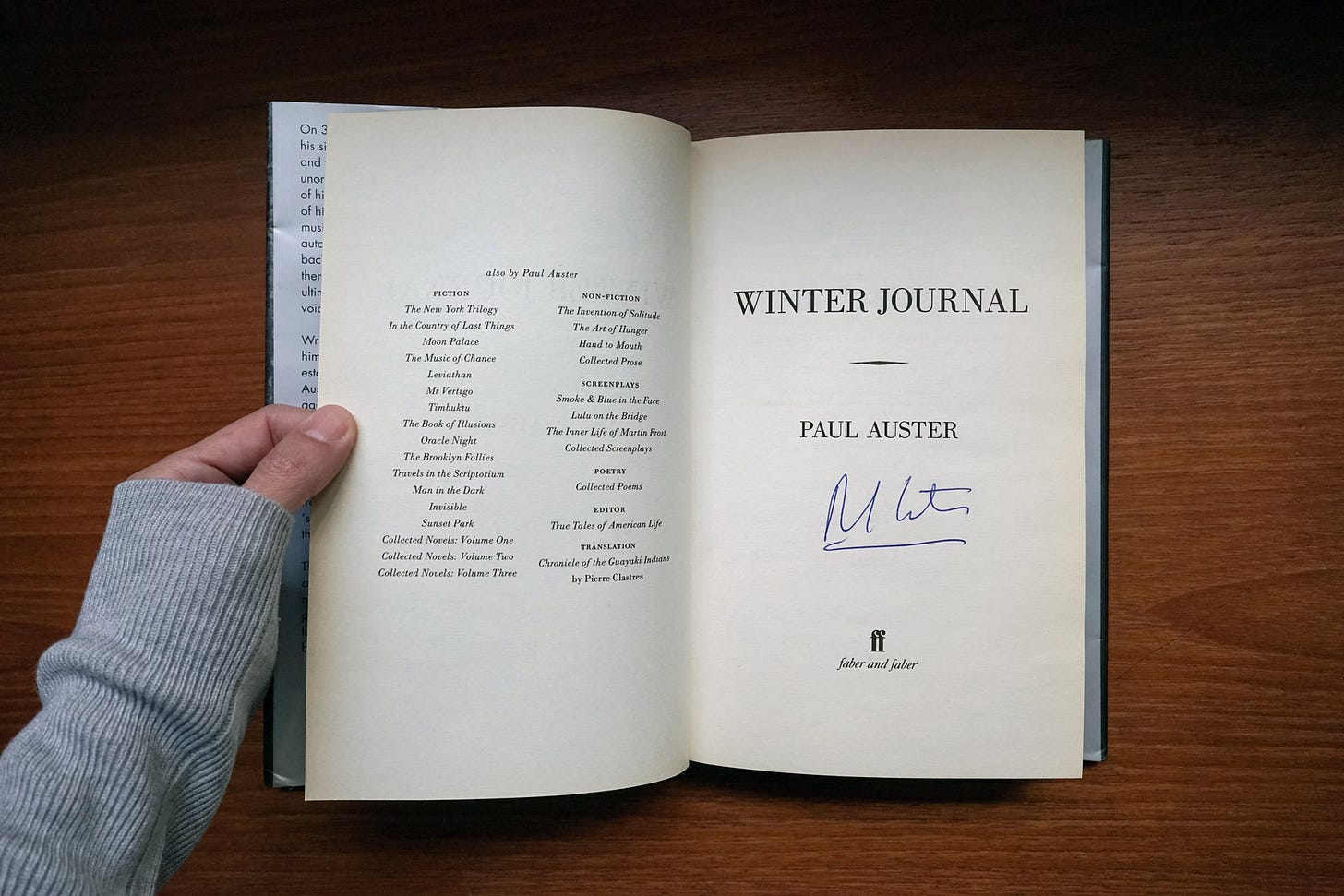

It was ten years ago, ‘Winter Journal’ freshly out of print, and Mr Auster was in Athens for a few days invited by the publishing house on the occasion of the Greek book launch. There was a book signing of course, and I went with my hardcover in hand and a handwritten note I had scribbled in haste that same morning. I sat among a crowd a bit disappointed by the meagre size of it but delighted I could sit a few feet away from him. How very strange, I thought, while he read a passage from his book; how very strange, I kept thinking during the whole time. When my turn came up for the signing I was so nervous I barely said hello as I slid my book towards him. Somehow though, I found the nerve to give him the envelope. I wanted to tell him, “It’s not a love letter, I promise, just a thank you note” but I just smiled and walked away. He was an impressive man, a handsome man, yes, but my words were not those of an infatuated girl. I wrote about that day in the bookstore and how much I admired his books – trite words I presume for a writer of his stature. My English must have been terrible at the time. I ended my note by saying, “Thank you for being who you are and writing the things you write.”

It was a love letter, now that I come to think about it. I hope he read it.

“You have to think of love as a kind of tree or a plant,” Auster says. “And that parts are going to wither and you might have to cut off a branch to sustain the overall growth of the organism. If you get fixated on keeping it exactly as it was, one day it will die in front of your eyes. For a love to be sustained it has to be organic. You have to keep developing as it goes along so everything is all intertwined, even the sheer strangeness of it all.”

* * *

He was a uniquely American man of letters who was rarely afraid of experimentation, unlike others.

I enjoyed reading this.

The following is an excerpt from an interview he had with Louisiana Channel, which is so beautiful and true, and sounds like a legacy.

“The essence of being an artist is to confront the thing you’re trying to do. To tackle it head on. And if, in wrestling with these things, you manage to make something that’s good, it will have its own beauty. But it’s not a kind of beauty that you can predict. You know, it’s nothing you can strive for. What you have to strive for is to engage with your material as deeply as you can. Even if it’s, you know, funny. Even if you’re trying to be funny, you have to engage with it as deeply as you can. And I think this is why -- or this is how, I think -- I justify to myself how I’ve spent my life. Which is a very strange way to live -- alone in a room every day, putting words on pieces of paper. Wow, a lot of other things I can think of would be more amusing to do, and more meaningful to the world. But the thing about doing this, which is unlike any other job, is that you have to give maximum effort all the time. You can’t slack off. You have to give every ounce of your being to what you’re doing. And I don’t think there are many jobs that require that. You see lazy lawyers, lazy doctors, lazy judges. They can get through things -- you even see lazy athletes, who are just not making maximum effort all the time. But you can’t be a writer, or a painter or a musician, unless you make maximum effort. So, I can get up from a day’s work, and I’ve done nothing. I’ve crossed out every sentence I’ve written, crumpled up pieces of paper, thrown them into the garbage can, and I’ve nothing to show for it. But I can at least stand up and say, at the end of the day, I gave it everything I have, I’ve tried 100%. And there’s something satisfying about that. Just trying, as hard as you can, to do something.”